Web3: an indie game dev perspective

I was curious to explore Web3 because the movement touches on several things I care about: new revenue streams for artists, decentralization, and fully-realized virtual worlds. The following piece analyzes three concepts central to Web3 from my vantage point as an independent game developer.

Introduction: Defining “Web3” and “Indie”.

Web3 means different things to different people. To some, Web3 means “an ecosystem of applications running on the blockchain.” Others see Web3 as a movement experimenting with a series of loose but connected ideals, design patterns, and technologies whose broad goal is to build a new, better Internet on core principles such as equity, digital ownership, decentralization, and interoperability.

It is this second framing that interests me. Within this framing of Web3 as an experimental movement, ideas are still in their nascent stages, certain concepts may conflict, and various Web3 communities are messily figuring out together what it all means, and how it will all work. In this framing, there’s still room to interrogate and reject antipatterns, as opposed to converging on the inevitability of a particular Web3 stack.

From this position, I aim to assess three concepts associated with Web3: interoperability, decentralization, and artist support. I chose these particular concepts because they’re interesting to me as a game maker, and we’ll examine each of them through the lens of a short game prototype I made to go along with this essay.

I aim to assess three concepts associated with Web3: interoperability, decentralization, and artist support. I chose these particular concepts because they're interesting to me as a game maker.

We’ll be looking at these concepts primarily from the perspective of a small indie, which I define as a studio of 10 full-time people or less. From here on out, I’ll be using the term “indies” to refer to both creators and fans of indie games interchangeably.

We’ll be focusing on indies who make premium titles–games you pay for once, as opposed to free-to-play games with microtransactions. (The F2P->P2E corridor is a vast topic deserving of its own analysis.) In this essay, I want to focus on small teams that make games as art: unique experiences that focus on elements such as novel mechanics, rich story, and distinctive art style. Such games run the gamut from first-person shooters to visual novels, and they’re primarily distributed via the platforms Steam and Itch.

Although small indie teams can make multiplayer games, the majority of small indie projects are single-player, especially if they’re made by a solo dev. For this reason, we’ll be looking at a short single-player game prototype that I created as our case study for understanding the current status of the indie world’s relationship to decentralization, interoperability, and artist support.

The Game Prototype: Everlast

To examine decentralization, interoperability, and artist support from the perspective of an indie, I created a short prototype for a game to illustrate some of the points I'll be making below.

To examine decentralization, interoperability, and artist support from the perspective of an indie, I created a short prototype for an FMV (full-motion video) game to illustrate some of the points I'll be making below. This 10-minute prototype represents the type of game that a solo dev might be able to ship on their own within several months.

Everlast is a short, interactive sci-fi story about a future metaverse run by corporations. You play as a recently-deceased human who is being onboarded to your digital afterlife. The gameplay happens in the form of branching narrative; a choose-your-own-adventure style of gameplay in which you progress through the story by making choices.

To create this game, I first created a text-only prototype using Ink, a free framework for writing interactive text stories. Then I did a round of playtesting, taking note of moments when players were confused, frustrated or hoping for more choices.

After iterating on my script in Ink based on player feedback, I moved the project into Unity, a free game engine. Within Unity, I used Charles Engine, a toolkit specifically for making FMV games. All of the footage in the game is generated using machine learning; I used Synthesia, an AI video generation platform where you can turn text prompts into videos of people talking.

The final game can be played here:

New Forms of Revenue

One of the biggest problems facing indies is sustainability. Many small studios struggle to stay afloat due to financial instability. Only 3.5%-6% of indie games that sell on Steam generate enough revenue to fund a follow-up project. The high rate of failure for small indies can be attributed to several factors: a saturated market, rising development costs, and a lack of publisher support.

Some have proposed that NFTs could open up new revenue streams for game devs. Due to its digital nature, game art, especially that of the 3D variety, hypothetically lends itself well to the format of tokenized collectibles. Using Everlast as an example, one approach could be to create new videos featuring my game’s main AI character, and selling those clips as NFTs (if Synthesia’s TOS didn’t expressly forbid such usage). However, there are a few problems with this approach, and they have to do with a shift in indies’ conceptualization of crypto that occurred over the past decade.

The indie community has always been excited to experiment with new technologies. In 2014, game developers on Itch, a platform catering exclusively to indies, started to request the ability to accept cryptocurrency. The following year, Itch announced Bitcoin support, citing it as a highly-requested feature. In 2022, Itch tweeted, “NFTs are a scam. If you think they are legitimately useful for anything other than the exploitation of creators, financial scams, and the destruction of the planet then we ask that you please re-evaluate your life choices.” Around the same time, an industry report conducted by the Game Developers Conference revealed that 70% of devs reported being uninterested in NFTs, and 72% reported being uninterested in cryptocurrency.

What happened between 2014 and 2022? Two things: indies became aware of the environmental impact of the proof-of-work blockchain, and they began to view crypto as technology facilitating the concentration of power, rather than diffusing it.

Web3’s intention to normalize the direct financial support of artists by fans remains one of its most endearing qualities–but as long as that intention remains intertwined with proof-of-work blockchain and design patterns that encourage financial speculation, it will never be embraced by indies.

Indie games and climate consciousness have long been intertwined. Climate change comes up as a perennial theme in indie games, with titles such as Norco and Frostpunk exploring the devastating effects of pollution on our world. Leading up to the explosion of crypto, indies were already contending with some difficult conclusions around the climate cost of both gaming and game-making. For this reason, indies are often strongly opposed to adopting any new technology that carries a high environmental cost. While there are potential ways to mitigate blockchain’s carbon footprint, they have yet to be implemented at scale. Even if Ethereum pivoted to proof-of-stake tomorrow, for much of the indie space, the damage may be irreversible: blockchain carries such a powerful association with ecological disaster that many would be loath to adopt it even if it were environmentally friendly.

Secondly, indies are deeply distrustful of the NFT concept because they worry that adopting the paradigm puts them at risk of becoming both victims of and complicit in pyramid schemes. News stories of scams and hacks make it difficult for indies to take blockchain seriously as a viable tool for building trust with their audiences. Beyond scamming by low-level bad actors, Ethereum itself is viewed by many indies as the ultimate Ponzi scheme, in which the primary beneficiaries are the shareholders and leadership of companies that traffic in Ethereum-based transactions. Tracking secondary market sales and giving profit to the original artist remains a compelling proposition, but on the flip side, indies are hesitant to adopt a business model that’s reliant on speculation because within that framework, they worry that down the line, some of their supporters will get burned.

In summation, Web3’s intention to normalize the direct financial support of artists by fans remains one of its most endearing qualities–but as long as that intention remains intertwined with proof-of-work blockchain and design patterns that encourage financial speculation, it will never be embraced by the indie dev community as an ecosystem. If Web3 is to be inclusive of indies, it must abandon these antipatterns and explore other avenues in its mission to create sustainable income for artists.

Decentralization, Part 1: The Game Relying on centralized platforms carries both benefits and risks for indie devs. The biggest benefits remain discoverability and reach. The biggest downsides are fees and censorship. Most platforms charge a fee to list games, and then take a cut of each sale. This can be as high as 30% for Steam, making it difficult for indies to make a profit. Some platforms have strict content rules that can have a chilling effect on creativity. Apple’s rules are perhaps the most strict, as they prohibit any kind of nudity or graphic violence in games. On a more conceptual level, centralization of the video game industry poses an existential threat to indies. Larger companies threaten to absorb or squeeze out smaller teams, endangering an ecosystem of diverse and innovative gameplay. In Web3, the word “decentralized” has many different meanings. It can convey a general ethos of autonomy and independence, describe the desire to redistribute wealth more equitably, or it can refer to the traits of specific technologies such as blockchains. When it comes to the more general ethos of decentralization, I believe that indies and Web3 proponents are aligned. People in both groups want new systems that are transparent, equitable, and resilient against concentrations of power.

Centralization of the video game industry poses an existential threat to indies. Larger companies threaten to absorb or squeeze out smaller teams, endangering an ecosystem of diverse and innovative gameplay

When it comes to specifics, things become a little more nebulous. If we’re not talking about interacting with decentralized currency for reasons cited in the section “New Forms of Revenue” above, we’re left with the concept of combatting the centralizing force of platforms. If I were to attempt to bypass platforms in an effort to distribute Everlast, I could sell copies of the game directly to audiences off my own server. Unfortunately, most gamers want to purchase their games directly on Steam, because they like for the game to appear in their Stream library. Some developers have attempted to work around this problem by selling Steam keys directly from their sites, bypassing the platform’s 30% cut. However, this remains an unappealing proposition for all but the most devoted of fans due to the perceived effort involved in signing up for a new site, typing in credit card details, obtaining a Steam key, and then going over to Steam to download the game. Anecdotally, most developers I know have stopped doing game sales this way because the demand just isn’t there. This speaks to an unfortunate reality: the average user doesn’t want or care about decentralization. Not in terms of their user experience, and certainly not in terms of backend protocols. It's mainly for this reason that previous Web 2.0-era attempts to decentralize the web, such Mastodon and Diaspora, largely failed. Bypassing the centralizing force of Steam and other platforms remains an unsolved challenge for indies because it’s not what users want. A similar phenomenon is occurring in the Web3 space, with the ecosystem strongly trending toward consolidation around a few key players such as Etherscsan, Infura, Coinbase, and Opensea. Decentralization remains a worthy conceptual goal, but decentralized technology protocols don’t appear to have led to a truly distributed ecosystem in practice, as described in cryptographer Moxie Marlinspike’s essay “My first impressions of web3”. Decentralization, Part 2: The Studio What about decentralizing the game studio itself? DAOs offer some compelling design patterns for operating game studios as leaderless collectives. Some Web3 proponents have gone even further than that, describing DAOs in which fans co-create game worlds together with professional devs by voting on creative directions through governance tokens. Indie studios have been forging their own paths towards similar styles of decentralization independantly of the Web3 movement, allowing for shared value amongst workers and audiences. Worker-owned coops are gaining traction as a studio operating model. In recent years, high-profile studios that have adopted this model include Skullgirls developer Future Club, Dead Cells developer Motion Twin, and The Glory Society, a co-op formed by the co-creators of Night in the Woods. There has also been a trend of sharing game ownership with the audience: some indies now crowdfund games through Fig, a platform that lets fans share in a game’s revenue in exchange for funding it. Many people define a DAO as a Discord with a bank account and a cap table. I believe that this conceptualization of a DAO could be interesting for more indies to experiment with. However, if a DAO is a Discord with a bank account, but that bank account runs on Ethereum, that’s where it gets dicey, again for reasons described in section “New Forms of Revenue”. Indie studios have been forging their own paths towards decentralization independantly of the Web3 movement, allowing for shared value amongst workers and audiences.

Luckily, one doesn’t need the blockchain in order to run a leaderless collective, provide mechanisms for member voting, or fractionally share in the output of that collective. We have all the coding resources needed to make this happen without introducing a distributed ledger into the equation. Such a collective could still secure its data cryptographically on a centralized server, and publish publicly-available logs of every vote, decision, and transaction for transparency. Looking at it through the lens of Everlast, I could set up a token-gated Discord where fans of the game could vote on new characters or new story branches using those tokens, which could be released as new serialized mini-games whose revenue could be shared amongst its contributors. The tokens could be sold for regular fiat currency, and the voting ledger could just live on a regular server. This would lower the barrier to entry for blockchain-averse fans of indie games who want to participate in this style of transparent, collaborative game-making. Interoperability Interoperability is interesting to indies because it facilitates the emergence of cross-media worlds. A decade ago, the popular educational gamedev series Extra Credits waxed poetic about the the potential of interoperability to close the gap between casual and hardcore players, allowing them to participate in shared gaming experiences: “if my mom could harvest her farm to give me crafting regions in my MMO; if your girlfriend or boyfriend could play Bejeweled to repair your armor; if I could play my grand strategy game to bring back resources that my friends needed to construct their towns, which in turn helps me recruit more units; if I could capture foreign monuments for my friends to erect in their Sim City, how cool would that be?” The concept of interoperability has been a long-standing area of interest for game academics as well. A 2011 paper titled “Interoperability in Serious Games,” argues for the establishment of cross-discipline standards for the interoperability for complex systemic models across educational simulation games. To imagine today’s interoperability pipeline and extrapolate on it, we must first understand the anatomy of a typical game asset.

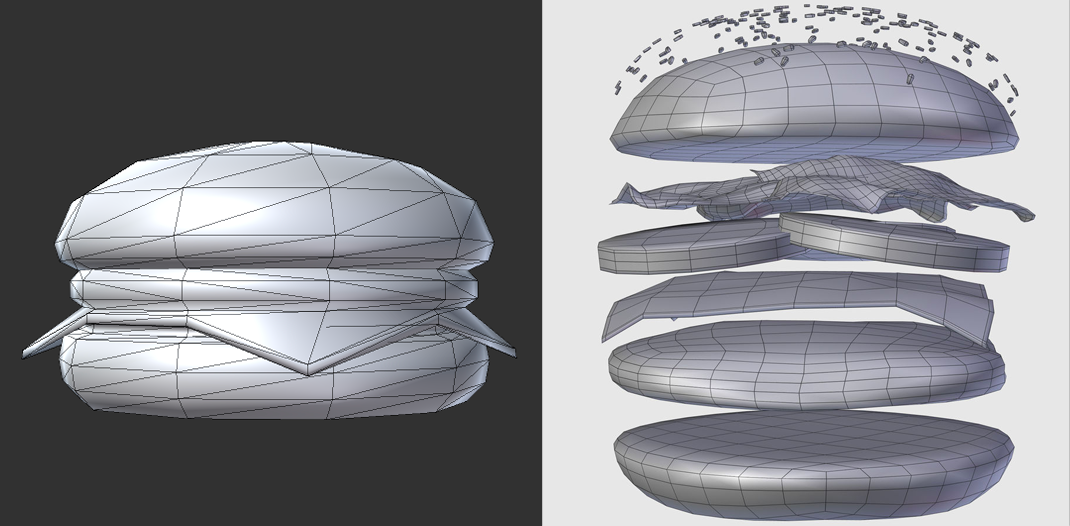

Interoperability is a key concept in Web3 as well. Once more using Everlast as an example, let’s look at how interoperability, as imagined in Web3’s canonical example of “transferring a sword between two games,” would unfold. At one point during your playthrough of Everlast, your player-character receives one cheeseburger in their inventory. Let’s imagine that a player of Everlast wants to use that burger in another hypothetical game–a food fight game in which the burger can be deployed as a weapon. How would this work today? To imagine today’s interoperability pipeline and extrapolate on it, we must first understand the anatomy of a typical game asset. At their most basic level, 3D assets are composed of polygon meshes and texture maps. A simple game asset might have only one texture map, while a more complex item might have multiple texture maps layered on top of one another to make the object look more realistic: these include bump maps, specular maps, displacement maps, etc. Game assets might also have multiple textures that vary in detail and swap out dynamically at runtime depending on how close you are to that object in the game. In addition to textures, some game objects have shaders, which are small scripts that typically handle the way that object’s surface reflects, emits, and absorbs light in accordance to the rules of that game’s lighting system. Each game engine simulates lighting in a different way, making it necessary for a developer to rebuild shaders when moving an asset between two game engines. Game objects also have some combination of programmed behavior, sound effects, animation effects, rigging, and a myriad of other custom attributes. Going back to the cheeseburger in Everlast, let’s imagine that for my game, the asset consists of one solid mesh, meaning that the lettuce, cheese, onions, patty and buns are fused together into one blob, and covered by one texture map. I did it this way because I wanted the asset to be simple. Now imagine that in the food fighting game I’d like to be interoperable with, the burger needs to dramatically fly apart on impact after you hurl it at your opponent, sending all the layers of the burger flying in opposite directions. That asset would need to be composed in a totally different way, with each layer of the burger appearing as its own mesh, and each mesh requiring its own texture map. Of course, you can’t currently store such a complex collection of files as an NFT. Even if you could, the amount of manual coordination, asset recreation and coding required between me and the developers of the second game would be significantly labor-intensive. The above was a relatively simple example of the kind of work that goes into transferring one asset across two games, but the complexity ramps up exponentially from there as you consider game objects with more robust behavior. For further reference, see:

I often see the argument above used to support assertions that game interoperability at scale is an impractical pipe dream that will never happen. In the short term, I think that is correct. In the long term, I think this view is pessimistic–although, to be fair, few people on either side of this debate are clear about the exact timeframes within which their arguments apply. When evaluating the issue through the lens of current game-making tools and workflows, it’s easy to arrive at a conservative outlook. But it’s important to remember that games are only a subset of tech, and that a lot of people are exploring new approaches to interoperability and creative tools from many different vantage points. On the art creation side, I believe that game asset pipelines will be drastically automated by machine learning. When I consider that two years ago, I had to open a specialized 3D program in order to model an object, and that now I can simply type in a text prompt and have a GAN generate a 3D mesh, I feel optimistic. The tech is rudimentary at the moment, but in a few years, our tools and workflows for making and managing game art will be much more efficient and user-friendly, reducing the human touch needed to facilitate interoperability. One day, I’ll be able to show a GAN my one-mesh cheeseburger and say, “make me this, but with all the layers in the burger as separate meshes with their own texture maps,” or “give me this sword, but in the low-poly pastel style of this other game.” In addition to asset generation, I believe that ML will one day be able to ease the coding burden involved in interoperability as well. Does the tech I just described “solve” the problem of interoperability? No. It’s not even fully baked yet, and there will also need to be effort to streamline everything from game engines to coding best practices to legal standards for managing IP licensing for interoperability to emerge at scale. But all the areas I just described have experienced rapid shifts over the past decade, and I believe that the pace of progress will accelerate. I predict that we’ll have a world of overlapping, interoperable game spaces in the next 15 years, and that it will indeed be magical. It’s worth reflecting just on how little blockchain has come up in my analysis of interoperability. That is because blockchain in no way functionally solves any of interoperability’s hard problems. Securely tracking who owns what is the one piece of this puzzle that has been solved for a long time. Conclusion Based on the above analysis, I believe that in order to move forward in a way that's inclusive to more creators across different mediums, the Web3 movement must abandon the core thesis that blockchain needs to underlie a better Internet. In my view, you don't truly need the blockchain in order to run a DAO, have programmable money, move objects between virtual worlds, or sell digital goods. Blockchain does have some legitimate theoretical uses, such as combating deepfakes and helping refugees flee repressive regimes with their assets intact. But that doesn't mean we have to kludge it into every part of a new ecosystem. What's the point of taking one of our most abundant resources – computing – and making it artificially scarce across the board? In addition, I believe that centering on design patterns that encourage financial speculation in Web3 products is a mistake. My worry is that these kinds of design patterns don't scale, that they incentivize shady behavior, and that they might lead to disappointment for many down the line.